Communities of Practice

Buzz Words

I was looking back at some of the blogs on the IPLA website and one comment stirred a lot of thinking. Why do teachers not like jargon or statements that on the surface do not appear to mean anything. In effect, this comment had brought to the fore an important dimension in physical education that we do not address.

We have a major division between academia and professional practice in schools. Academics have to undertake research and publish their work in journals dedicated to this purpose but they are usually too expensive for teachers, inaccessible and rarely address issues of immediate concern to teachers. Academic careers are founded on this process and it is very understandable that many of the brightest minds go into work because it can be rewarding.

One year ago I was listening to a research presentation that was fascinating and full of ideas relevant to teaching and learning. I asked the scholar did he intend to publish this work so that it was accessible to teachers. His response stunned me because his reply was ”that is not my job, someone else has to do that”. Is this standard practice? So I looked through a number of journals and expensive books and it was difficult to find concrete examples that I could use in professional practice even though there were numerous ideas with potential. Then I explored a number of key names in physical education and looked for good professional advice based on their research. It wasn’t in academic journals but social media and personal websites that I began to find real gems and nuggets of original and inspiring ideas with direct relevance to professional practice. Nevertheless, how far can this penetrate into the world of professional practice?

Of course, academics will speak out and say that impact factors represent important aspects of their work now and I agree but this development has a long way to go before it has direct impact in schools and on professional practice. Translational work is seen also as a new initiative that could be relevant to practice but I feel that the authors need to understand practice and the realties of teaching day to day. Lawrence Stenhouse made an important point when he said that “all ideas need to be disciplined by the problems of practice before they can be curriculum initiatives that teachers can work with” (In a taped interview just a few days before he tragically died and one that has inspired me ever since).

Bridging the Divide

Has this division stimulated any research to solve the problem? I doubt it but it does raise another issue that may help us to understand the problem. In order to answer this I need to go back many years. In the 1980s I was working on a new curriculum model called MAN: A Course of Study (MACOS) recognised as the best pedagogical and research inspired project drawn from different disciplines. This was a unique experience and it has affected me throughout my career. If we tried to undertake an innovation using this approach, it would require at least 3 years preparation period, a shared understanding of all the disciplinary contributions (very high level scientists and academics) and the development of a clear position on children’s learning (Bruner et al). In addition, we would have to address what this implies in terms of appropriate pedagogy to guide practice and match the academic input (this was very strong throughout the project). Put all this together with a thoroughly planned training programme (18 months in planning) in which teachers experience the same learning methods that could be used with children. It cost $3 million in 1970s money. Today, we could never match this but it does illustrate the nature of the task and what is required.

However, I think we could spark something. If we could bring together all the best work of all the relevant disciplines into a theoretical framework and translate them into usable forms that can demonstrate the value and relevance of their work into a practice framework that can inform professional practice. It would open up a genuine feeling that we are getting there.

However, we need the same sort of shared understanding of individual disciplined forms that informed MACOS. To achieve this all the diverse disciplinary forms (and there are many of them) that currently exist within sport and exercise sciences need to recognise that their important work needs to have impact and have relevance to professional practice and public interest. This is happening in the Sciences stimulated by television documentary programmes supported by Royal Societies with a new commission tasked with reaching the public and making new research accessible to them.

In the same way, people working in professional practice need to be able to understand and ascertain exactly what theoretical positions and their implications are relevant to their practical work and what specific features of practice are key? How can these ideas develop into a practical framework that clearly marks the essential features and structure of a specific approach. In other words all the different approaches to the teaching of games (of which there are many) need to be clearly articulated and laid out in practical forms (this is beginning to happen on the TGFU website). This would enable teachers and researchers to clearly understand what is on offer and display their relevance to a more grand theory of how to teach and help young learn games. When I see the youtube clips that display these approaches I simply cringe at the quality and the misunderstandings that they display, including the bad practice that they illustrate so publicly. These practical interpretations often display conflicting messages and inappropriate pedagogy that is a major barrier for teachers seeking inspiration and ideas to develop their practice.

These tasks represent major challenges but we need to make a start. As a result there is a project going round which is attempting to demonstrate how this can be achieved in Physical Literacy. Within the next year we should be able to publish this work. We haven’t forgotten professional practice and this will be on the agenda and put into operation very shortly.

Let me finish with an observation. If researchers cannot provide a comprehensive up-to-date picture of how their work can inform practice, how can we expect practitioners/teachers to develop informed practice and improve learning opportunities. They cannot do it on their own.

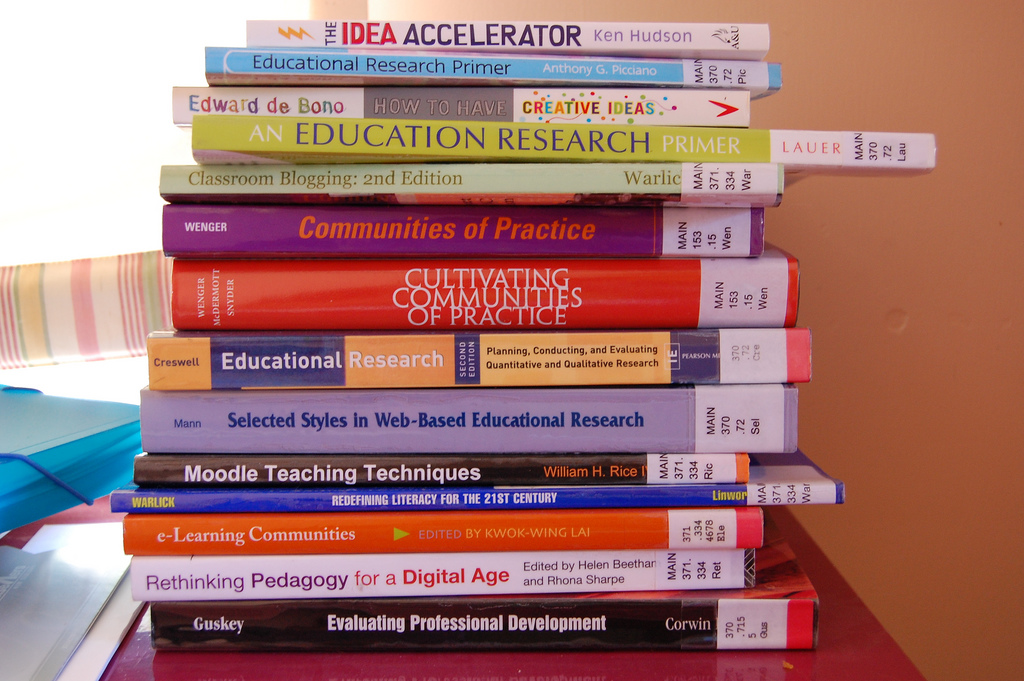

Photo: Catspyjamasnz